The Trench

Since its inauguration on 11 November 2011, the Great War Museum has become a key European reference on the First World War, with a unique collection of more than 70,000 artefacts and documents. It has received more than a million visitors to date and its rich and diverse collections, presented in an immersive scenography, have delighted both young and old – and especially schoolchildren and their teachers.

Today, the Museum hopes to offer even more and help the public to better understand the essence of one of the most emblematic symbols of the Great War – the trenches.

On 11 November 2024, it therefore inaugurated an open-air trench in its gardens. Visitors can walk through to better understand how the “trench system”, unique in military history, functioned. A second line, communication trenches, and a first line, offer an immersive experience, and visitors will explore an artillery post, a listening post, a dugout, a firestep, a tunnel entrance and, of course, no man’s land.

Ours is the first museum to offer such a comprehensive and immersive experience. This innovation is unique in France, and an opportunity to start a new page in the Museum’s history.

An immersive, innovative experience, designed to blend in with the museum’s architecture

The Great War Museum’s trench seeks to reconcile a perfect, full-scale scientific and historic representation of the trench systems with preservation of the Museum’s architectural and scenographic harmony.

The aim of the project is to give visitors a full understanding of the complex system of the trenches and the various spaces they were made up of, and thus provide context for the daily lives of the men in combat, preparations, how life was organized, and the time spent waiting. At the heart of the Museum’s gardens, between the two pillars on the hill the building was built on, the trench plays an essential role in the visitor experience. Its position makes it a focus of the visitor trail. You can see it from the forecourt and from the entrance hall and passageway, then go down to the heart of it to explore.

The visitor trail begins in the western passageway of the Museum, with a view over the trench. Visitors are welcomed as if they were new recruits and introduced to the battlefield before they enter. This introduction takes place at the rear of the second line, facing the “enemy”. The walkway is equipped with telescopes and signage offering in-depth information on the defensive and offensive systems and the various shelter areas, observation posts and first aid posts.

From this viewpoint, interpretation tools are available to present the trench system as a whole, the rear line and the perpendicular communication trenches leading to the first line. In the background, visitors can see a reconstructed no man’s land, with corkscrew pickets, chevaux de frise and barbed wire. A trail leads to a twisting staircase, and a lift for people with mobility difficulties, leading down into the trench. Like the soldiers of the Great War, visitors “go down” into the trenches.

The battlefield is logically entered from the rear, through a section of communication trench that opens onto the second line. As they follow a path of wooden duckboards, inspired by how trenches were floored but adapted to the constraints of public places and accessible to people with mobility difficulties, visitors explore a highly realistic trench decor. The path follows a loop, running from the second line to the first line via a first communication trench, then from the front to the rear lines via a second.

Visitors’ exploration is accompanied by a soundtrack of explosions, whistling bullets and cries, with 3D audio effects and subwoofers creating a fully immersive experience. You leave the trench via the existing forecourt of the Museum.

Trench map

ARTILLERY POST

From the end of 1914, trench warfare illustrated the importance of special artillery suitable for use in the trenches: sort-range and relatively light-weight, it would fire powerful projectiles on a high trajectory. This led to the creation of trench mortars, known as crapouillots.

OBSERVATION POST

Observation posts allowed soldiers to observe the battlefield and adversary (their main role), sound the alarm in the event of assaults or attacks, and guide artillery fire. This small battlefield construction had to be camouflaged and well protected (armoured dome or bunker). It would often have means of communication.

TUNNEL ENTRANCE

This one is a mine tunnel entrance: an underground tunnel dug by sappers to carve out a mine chamber under enemy trenches before causing an explosion. They could be either active or abandoned. Tunnel warfare, or mining, involved tunnelling under enemy positions and destroying them using explosives. Camouflets were used to neutralize enemy counter-mine tunnels.

EMBRASURE

These features were built into the design of trench profiles, incorporating a parapet and a parados. The parapet was an edge protecting the trench from enemy fire. It was made of soil and consolidated using sandbags. The parapet also included defensive features like firesteps, which were made out of wood, soil or sandbags and were used by soldiers as benches or firing positions. Soldiers were therefore protected and could lean against them to fire while resting the barrel of their rifles on the embrasures, which was less tiring. Embrasures were gaps in the parapet, which were left to observe the enemy and fire rifles. The parados protected fighters from behind and was formed of a bank of soil, sandbags, and a palisade of defensive stakes. The ground was often covered with duckboards, formed of wooden planks with gaps that were placed at the bottom of trenches to even out and consolidate the ground and enable soldiers to move around despite rain, mud and accumulating water.

DUGOUT

This was a front-line shelter that protected soldiers only from bad weather. They were cavities dug into the soil for one or two men.

MACHINE GUN POST

Machine gun positions could protect the trench leading to the listening post, from either side.

LISTENING POST

Listening posts were often advanced beyond the barbed wire, to about 50 metres forward of the trench. They were protected by their own small barbed wire network. They were accessible via a communication trench, which was either underground or covered with barbed wire. The listening post would be occupied by lookouts, and bombardiers or grenadiers. Soldiers deployed to the listening post were responsible for listening in on enemy activities and gathering intelligence, warning the trenches to the rear in the event of an assault, and holding out until the last moment with rifles and grenades. After withdrawing, the soldiers from the listening post would activate an automatic blocking system built into the listening post’s access trench.

NO MAN’S LAND

No man’s land was the neutral, devastated and uninhabited strip between the positions of the two adversaries. Its width would vary from a few dozen metres to a few hundred. The bodies of dead soldiers, various types of debris (ruins, remains of trees) and thousands of abandoned metal and wooden objects (such as cartridge cases, munitions crates, helmets, canteens and corkscrew pickets) were scattered across this cratered zone. Supporting defences were placed all across no man’s land, and particularly barbed wire. These defences, placed a few dozen metres forward of the trench over a strip about 10 metres wide, aimed to block, slow and channel the progress of the enemy. Countering these defences required destructive means (it took a large quantity of artillery munitions to destroy a section a few metres long) and designing ways to neutralize them (cutters, mobile shields, grappling hooks, and various explosive devices like strings of charges).

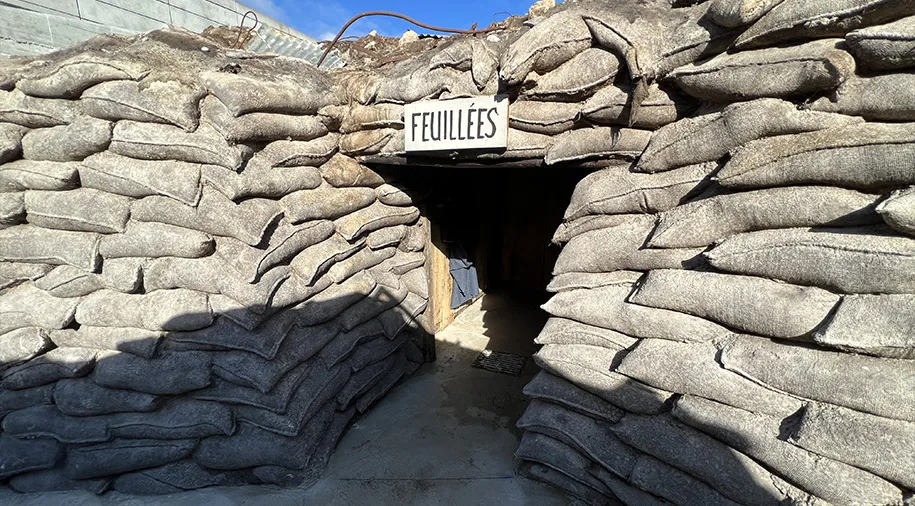

LATRINES

Rudimentary field latrines (holes, abandoned trenches) were used, which were hidden from sight with branches. They were accessed through special trenches. The holes were deep to avoid having to replace them too often.

SHELTER

Shelters were central to the daily lives of the soldiers. They lived there, and the quality of the construction was a question of life and death. There was a wide variety of shelters, ranging from basic holes covered with tarpaulins or canvas to deep underground constructions, sometimes with several levels, which were more comfortable, potentially built with concrete, and might even have electricity. Living conditions in the shelters varied considerably, depending on the nature of the terrain, the violence of the fighting, how long the shelters had been occupied, and soldiers’ rank.

Shelters were dug deep, always had one narrow entrance (occasionally a second), were often propped up with wood, and could be furnished (bunk beds, tables, chairs, candlesticks, etc.).

AID POST

We present here a small front line aid post, to provide initial treatment before evacuation to the rear.

PRACTICAL INFORMATION TO ACCESS TRENCH

- Opening hours of the Museum and the trench: The trench is accessible without a guide during the Museum’s opening hours (except between November and March, when it closes at 17:00). The Museum is open every day except Tuesday, 09:30 – 18:00. The visit to the trench lasts on average 30 to 45 minutes.

- Tickets: the free visit to the trench is included in the museum entrance ticket.

- Access: With your entrance ticket, the entrance to the trench is at the reception-shop level (1st floor) and the exit is on the forecourt (direction of visit to follow). The toilets are accessible on the ground floor.

In case of very bad weather (snow, hail, frost, storm), the museum may close access to the trench. In case of high attendance, the museum may limit access to the trench. - Accessibility: The trench is accessible to people with reduced mobility. Some areas allow seating.

- Permission and prohibition: Photos are allowed with flash. Drinking and eating are prohibited in the trench. In rainy weather, umbrellas are prohibited.

Interviews with the main players in the construction of the trench

Patrons who contributed to the construction of the trench

Find the presentation of the various partners and patrons in the press kit.