Exhibition Soldiers at play – Part 1: Sport: a tool to prepare soldiers

Gymnastics and the Hébert method

Since the second half of the 19th century, and particularly since France’s defeat by Prussia in 1870, the government has encouraged sport in school and military contexts in France so as to be able to build an army of trained soldiers ready for battle. Thanks to military service, physical exercise ceased to be a mere bourgeois occupation, giving each conscript the opportunity to develop their athletic prowess. Physical education was seen as a matter of health and morality and was central to the life of young soldiers. Alongside shooting and combat sports, gymnastics was a key part of training and was taught by instructors trained at the military gymnastics academy that was created in Joinville in 1852. This laid the groundwork for the “natural method” developed by the officer and physical trainer Georges Hébert. He advocated useful and functional exercise, a far cry from the static gymnastics that was often practiced before. This training method, which remains extremely popular today, is practiced in groups and in natural environments, most often with obstacles requiring participants to jump, crawl and run. It develops physical fitness and fosters mutual support and cooperation. Georges Hébert was also behind the design in 1915 of obstacle courses to train soldiers.

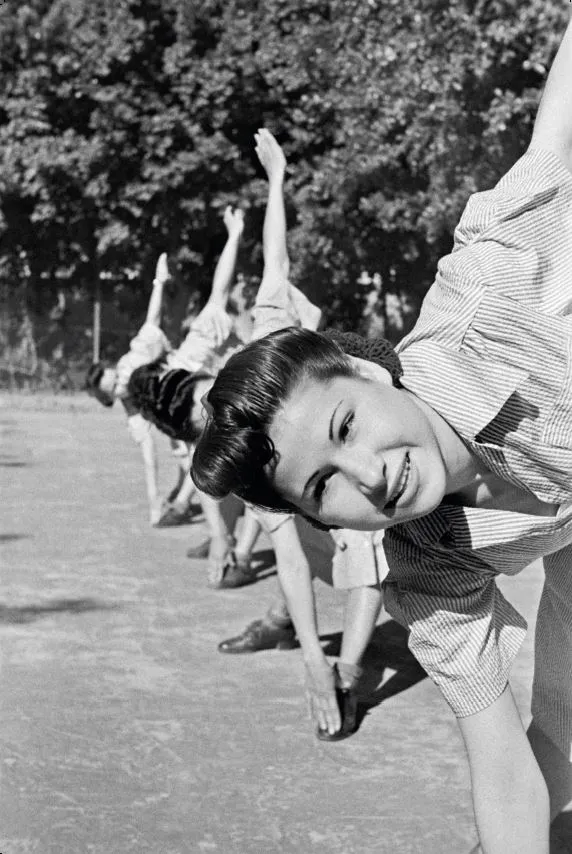

Sport for women in the army

During the Great War, many nurses served in the military for the first time, within the armed forces health service. The period also saw the emergence of true women’s sport, temporarily emancipated from that of the men. At the rear, several women-only events, competitions and clubs were formed. In 1917, for example, the Femina Sport club organized France’s first women’s football match. A year later, the first women’s football championship worldwide was held in Paris. However, starting in the late 1920s, the return to order brought back the traditional household structure, sending most women back to the home, far from physical exercises. Only with the Second World War would sport be associated with their military engagement. The “Paul Boncourt” Act of 11 July 1938 officially authorized their mobilization. After the 1940 armistice, women could join the Free French Forces (FFL) of General de Gaulle as Air Force volunteers, signals officers or ambulance drivers. The latter were encouraged to practice gymnastics, Hébert’s “natural method” exercises, and running. The “air women” recruited by the Free French Air Forces (FAFL) trained in the same disciplines, in addition to swimming, team sports and the high jump.

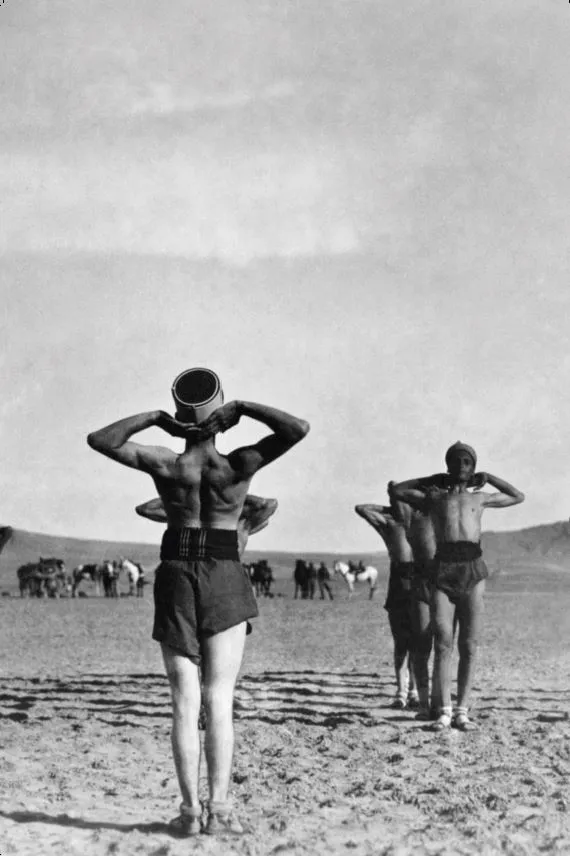

Bodybuilding in overseas operations

Individual training is part of the soldier’s daily life. It is estimated at about an hour a day and has a strategic goal: the soldier must be in full operational fitness. While sports training aimed in the first half of the 20th century to prepare soldiers for the fatigue and deprivations of war, today’s military physical education is part of a genuine policy. French soldiers’ physical education strategy was born in 1960 with the “Antibes doctrine”: the Military Physical Training Academy (EEPM) was based in the town, at Fort Carré. This doctrine, based on George Hébert’s natural method, focused on three types of exercise: general physical training, physical combat training in uniform and boots, and training that combined individual and team sports – often as leisure activities. Since the 1970s and the first overseas operations, these close ties between sports training and military physical preparation have been increasingly adapted to the nature of the mission. The material and temporal constraints of overseas operations require soldiers to engage in muscle training using what is available in their environment. This training remains essential to maintaining morale, physical and mental wellbeing and cohesion.

Sport and soldiers from France’s colonial Empire

In 1910, General Mangin advocated the mobilization of Africans from the colonies in the framework of European conflicts in La Force Noire (The Black Force). The incorporation of men from the colonial Empire into the French Army, from 1914 to 1918, aimed to have them contribute to the country’s common defence. In four years, just over 800,000 soldiers were recruited from across the Empire, from North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, Indochina, Tahiti and New Caledonia. Of them, 600,000 served in the infantry, across all fronts. In their preparation, “Zouaves”, “Spahis” and “tirailleurs” received conventional military physical education. It included gymnastics classes delivered by instructors trained at Joinville. During periods of leisure, they took part in games and sporting competitions organized by the regiments. Some would share their own sports, such as dance in the case of Senegalese riflemen. The globalization of sport, and football in particular, had been on the rise since the 1890s within the British Empire. After the war, it spread even further, with the return of French colonial soldiers to their regions of origin.